John F. Crowley: ‘We must further expand the state of possible’

On Wednesday, April 24, MassBio hosted the “State of Possible Conference,” considered “the ...

Read More LanzaTech x lululemon collab births a new sustainable fashion item

Athletic apparel retailer lululemon and biotech innovator LanzaTech have joined forces to create ...

Read More Company presentations at BIO 2024 inspire partnering

Company presentations at the BIO International Convention put innovators on stage before a ...

Read More Earth Day 2024 highlights need for plastic solutions

April 22 is Earth Day, a day that underscores the importance of conserving ...

Read More BIO Agriculture & Environment Summit brings together bipartisan policymakers, regulators

On April 18, BIO’s inaugural Agriculture & Environment Summit brought together bipartisan policymakers ...

Read More John F. Crowley: ‘Biotechnology is another word for hope’

On April 18, 2024, the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) held the inaugural Agriculture ...

Read More EDITORS' CHOICE

BIO Agriculture & Environment Summit brings together bipartisan policymakers, regulators

On April 18, BIO’s inaugural Agriculture & Environment Summit brought together bipartisan policymakers who emphasized the promise of innovation to address key challenges such as ...

April 19, 2024

Read More LATEST NEWS

BIO's View

John F. Crowley: ‘We must further expand the state of possible’

On Wednesday, April 24, MassBio hosted the “State of Possible Conference,” considered “the premier event for the Massachusetts life sciences industry.” Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) ...

April 24, 2024

Biomanufacturing

LanzaTech x lululemon collab births a new sustainable fashion item

Athletic apparel retailer lululemon and biotech innovator LanzaTech have joined forces to create a sustainable clothing item in a move to reduce pollution as well ...

April 24, 2024

Agriculture

Company presentations at BIO 2024 inspire partnering

Company presentations at the BIO International Convention put innovators on stage before a small but important audience, helping them engage in the networking and partnering ...

April 23, 2024

Biomanufacturing

Earth Day 2024 highlights need for plastic solutions

April 22 is Earth Day, a day that underscores the importance of conserving our environment and advocating for greater sustainability. It’s a call to action ...

April 22, 2024

Agriculture

BIO Agriculture & Environment Summit brings together bipartisan policymakers, regulators

On April 18, BIO’s inaugural Agriculture & Environment Summit brought together bipartisan policymakers who emphasized the promise of innovation to address key challenges such as ...

April 19, 2024

HEALTH

Company presentations at BIO 2024 inspire partnering

April 23, 2024

5 things to know for Primary Immunodeficiency Month

April 16, 2024

Biotech and One Health are key to controlling avian flu

April 15, 2024

Welcome, John F. Crowley!

Get to know John F. Crowley, the new President and CEO of the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO), in our exclusive interview.

AGRICULTURE

Company presentations at BIO 2024 inspire partnering

April 23, 2024

John F. Crowley: ‘Biotechnology is another word for hope’

April 18, 2024

Biotech and One Health are key to controlling avian flu

April 15, 2024

Climate Change

LanzaTech x lululemon collab births a new sustainable fashion item

April 24, 2024

Athletic apparel retailer lululemon and biotech innovator LanzaTech have joined forces to create a sustainable clothing item in a move ...

Read More Earth Day 2024 highlights need for plastic solutions

April 22, 2024

John F. Crowley: ‘Biotechnology is another word for hope’

April 18, 2024

Federal Policy

State Policy

Life Sciences PA recognizes John F. Crowley for biotech leadership

April 15, 2024

On April 10, Life Sciences PA awarded Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) President & CEO John F. Crowley the Hubert J.P. ...

Read More Colorado PDAB could limit patient access to medicines

March 20, 2024

New Mexico legislature passes clean fuel standard

February 19, 2024

International

5 reasons for investor optimism at BIO-Europe Spring 2024

March 29, 2024

WTO Ministerial ends, no expansion of COVID IP waiver

March 4, 2024

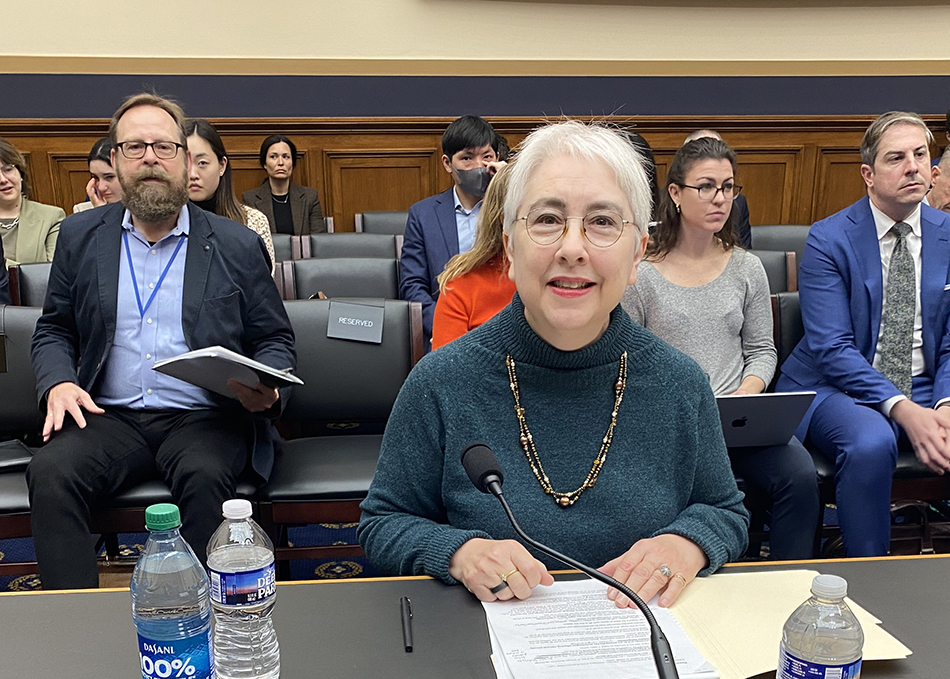

BIO Board member tells Congress WTO IP waivers hurt innovation

February 8, 2024

Bio's View

John F. Crowley: ‘We must further expand the state of possible’

April 24, 2024

On Wednesday, April 24, MassBio hosted the “State of Possible Conference,” considered “the premier event for the Massachusetts life sciences ...

Read More Company presentations at BIO 2024 inspire partnering

April 23, 2024

John F. Crowley: ‘Biotechnology is another word for hope’

April 18, 2024